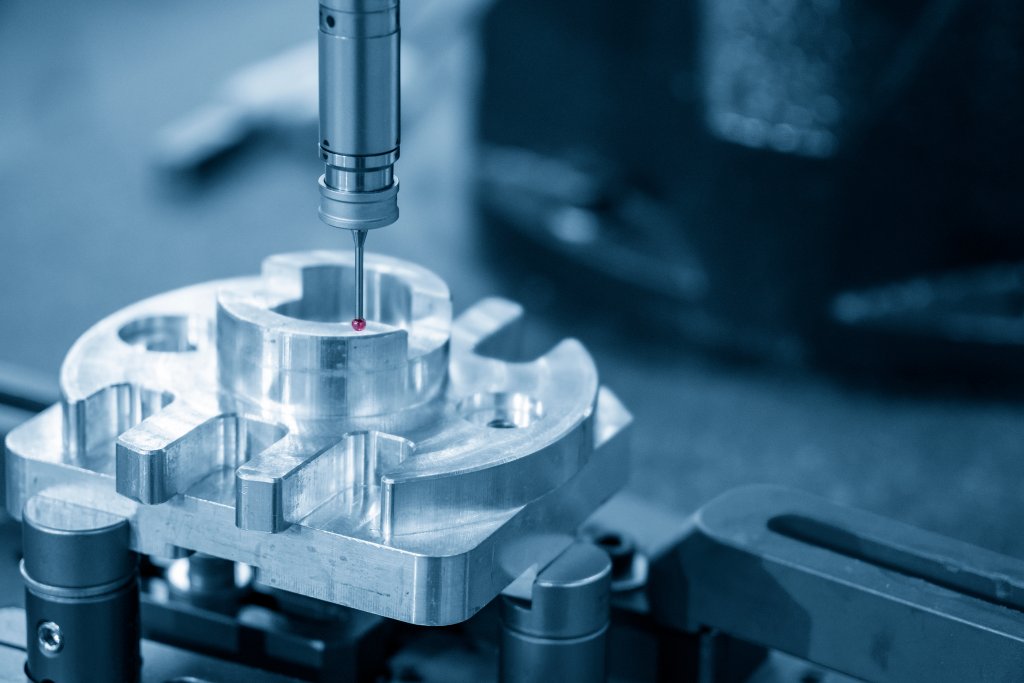

In aerospace manufacturing, deburring and finishing can be difficult problems to solve.

The challenge is removing burrs without changing the part dimensions.

As tolerances tighten and part complexity increases, finishing becomes less forgiving. A few tenths of unintended material removal can affect fit, seal integrity, or inspection results. This is why deburring is often treated cautiously—or pushed to the very end of the process—despite the risk that introduces.

Understanding how burrs form, and how different finishing methods interact with geometry, is critical to designing a process that removes unwanted material without compromising what matters.

Why Tolerance Loss Happens During Deburring and Finishing

Most tolerance issues are not caused by aggressive material removal. They come from lack of control.

Common contributors include:

- Manual pressure variation

- Tool stiffness that transfers force directly into the part

- Uncontrolled contact angles

- Repeated handling outside the machine

In practice, this often shows up as:

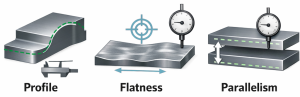

- Loss of flatness or parallelism

- Rounded edges where sharp edges are required

- Dimensional drift at mating surfaces

- Inconsistent inspection results across shifts

The more a process relies on operator technique rather than programmed behavior, the harder it becomes to predict the outcome.

Removal of Surface Peaks — Not Geometry

A key distinction in aerospace finishing is understanding what should be removed and what should not.

Peaks are localized material formed during machining. They are not part of the intended geometry, but they often sit directly on functional edges and surfaces. Removing those peaks without affecting the surrounding material requires a finishing method that is compliant, not rigid.

Rigid tools tend to:

- Transfer force directly into the part

- Follow geometry rather than selectively removing peaks

- Increase the risk of dimensional change

Compliant finishing tools, when properly applied, behave differently. They contact high points first and deflect before significant force is transferred into the underlying geometry. This makes it possible to remove peaks while preserving edge position, surface flatness, and critical dimensions.

Flatness and Parallelism: Where Things Go Wrong

Flatness and parallelism issues do not always originate during roughing or finishing passes. In many aerospace parts, achieving these specifications during initial machining is already difficult, especially as tolerances tighten and geometries become more complex.

Because those requirements are often only just met coming out of machining, finishing and deburring operations become a critical risk point. Even small, unintentional forces applied during secondary operations can push a feature out of specification. Hand deburring is a common source of this risk. Light, localized pressure can distort thin sections or subtly alter reference surfaces in ways that are not immediately visible, but often appear during inspection—or later, during assembly.

For high-tolerance aerospace components, finishing methods must:

- Apply consistent, controlled force

- Avoid concentrating pressure in a single area

- Be repeatable from part to part

Any process that lacks this level of control increases the likelihood of losing flatness or parallelism, regardless of how carefully it is performed.

Removing Burrs Without “Breaking” the Edge

Not all aerospace edges should be rounded. In many cases, edges are specified to remain sharp, with only minimal burr removal allowed.

This is where uncontrolled deburring causes problems. Traditional approaches often remove material indiscriminately, turning burr removal into unintended edge modification.

Controlled brushing processes allow manufacturers to:

- Remove burrs while maintaining edge location

- Apply a consistent, predictable edge break when required

- Preserve sharp edges where specified

- Avoid over-processing sensitive features

The goal is to preserve the part while removing what does not belong.

Keeping Finishing Inside the CNC

One of the most effective ways to protect tolerances is to keep deburring and finishing inside the CNC process.

In-machine finishing offers several advantages:

- Tool paths are programmed and repeatable

- Contact force is consistent

- Part orientation is controlled

- Handling is minimized

- Results are predictable across machines and shifts

When finishing becomes just another programmed operation, it stops being a variable and starts being part of the process design.

Designing for Predictability, Not Correction

In aerospace manufacturing, finishing should not be a corrective step. It should be a controlled operation designed into the process from the beginning.

Processes that rely on manual intervention to “fix” burrs or edges introduce uncertainty late in production—exactly where risk is highest.

By selecting finishing methods that remove peaks without altering geometry, manufacturers can:

- Maintain tight tolerances

- Protect flatness and parallelism

- Reduce inspection failures

- Eliminate late-stage surprises

Deburring does not have to be a compromise. When it is controlled, compliant, and repeatable, it becomes just another predictable part of a high-quality aerospace machining process.

We Can Help Eliminate Late-Stage Risks

Our Application Specialists can help identify a controllable and consistent finishing solution for your processes. Reach out to us to get started.